Welcome to Cathode Ray Mission, veteran critic David O’Connell’s semi-regular deep dive into the history of genre television. Here you’ll find everything from Gerry Anderson puppets to long-forgotten horror anthologies, one-season wonders, long-running classics, and more – the weirder and more obscure the better. Long live the new flesh!

Creator: Joe Ahearne

Creator: Joe Ahearne

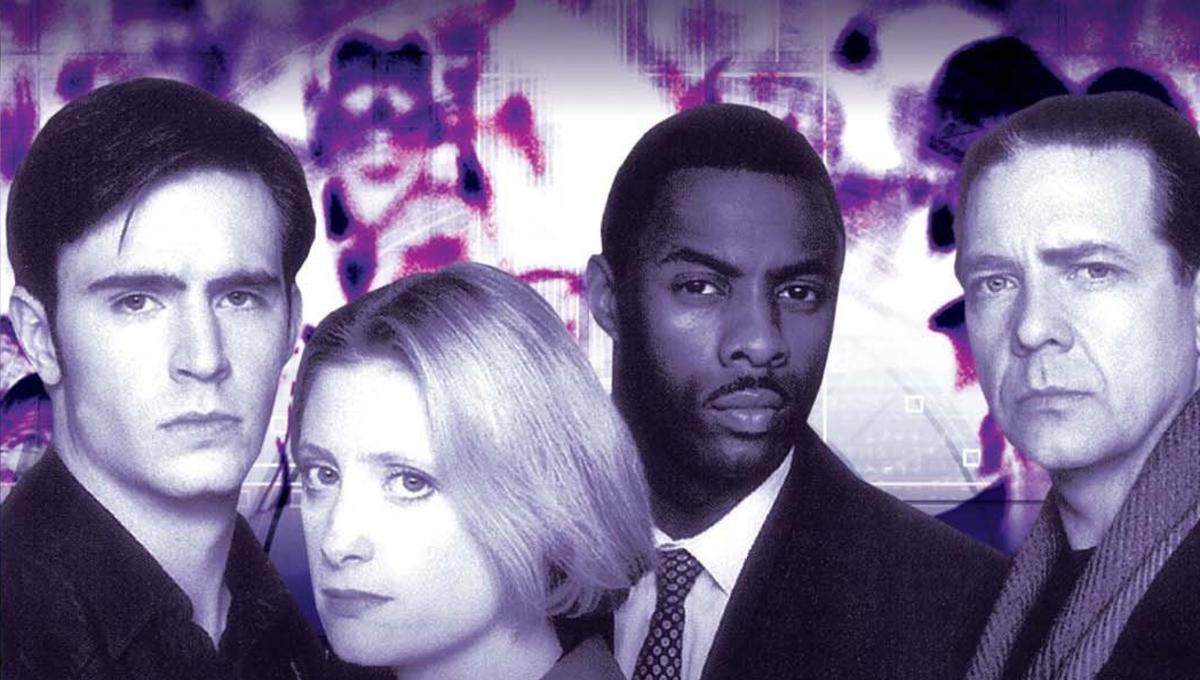

Stars: Jack Davenport, Susannah Harker, Idris Elba

When Detective Sergeant Michael Colefield’s (Jack Davenport) partner goes missing on his wedding day and an informant ends up murdered, Michael tries to seek answers as to what he was up to. What he uncovers is a conspiracy within the metropolitan police, a small dedicated team waging a secret war against a nocturnal enemy, an enemy that casts no reflection, and exists on human blood. An enemy referred to as “Code 5”.

Okay, the term makes more sense in roman numerals (Code V), but the enemy fought against are obviously vampires. Ultraviolet may belong to an era when a serious treatment of horror often lead to a reluctance to use the standard terminology for the monster, but don’t let that affectation fool you – Ultraviolet is quality viewing.

I mean it’s hard to knock the horror credentials of this six episode 1998 UK paranormal series, when they cast the great-great-granddaughter of Bram Stoker’s inspiration for Johnathan Harker in a major role. Susannah Harker, probably best known for the original 1990 version of House of Cards (the one we can still watch), plays Dr Angela March, the voice of scientific reason within the small group. She’s part of an exceptional cast that serves as the core cadre of the show. Jack Davenport, just prior to Coupling and Pirates of the Caribbean fame, plays our point of entry character, allowing the strange world to slowly unfold to audiences as he learns the abilities and scope of the “leeches’” plan, as well as providing an experienced investigator to the team. Australian actor Phillip Quast (The Devil’s Double, Hacksaw Ridge) brings appropriate quiet gravitas to the Father Harman, nominal head of the operation, and probably the member with the most long term experience with the conflict. Finally there’s an early role for Idris Elba (Thor, Pacific Rim, Luther), as the ex-soldier Vaughan Rice, the most no-nonsense member of the team, committed to a policy of vampire extermination.

Perhaps one of the most realistic approaches taken to the vampire genre, Ultraviolet treats the subject with the po-faced solemnity of a British procedural drama, and a very light touch on the lore. The result is exceptional, creating something that is compelling viewing, with an appeal that reaches beyond horror fans and genre aficionados. It’s clever, innovative and plays the supernatural in such a realistic manner that it almost becomes believable.

Perhaps one of the most realistic approaches taken to the vampire genre, Ultraviolet treats the subject with the po-faced solemnity of a British procedural drama, and a very light touch on the lore. The result is exceptional, creating something that is compelling viewing, with an appeal that reaches beyond horror fans and genre aficionados. It’s clever, innovative and plays the supernatural in such a realistic manner that it almost becomes believable.

The adaptations made to face this supernatural horror are also interesting, as the unit tailors technology to keep them in the fight. Carbon bullets instead of stakes, garlic (allicin) infused tear gas, UV-protected vaults, and video sight to confirm the subject is indeed a vampire (vampires don’t show up in reflections). It’s a response to a threat approached on a governmental and military level. As for religion, well, that’s a matter of faith, both for the vampires and for humans, therefore not a reliable deterrent.

Similarly, the vampires are obsessed with innovation. From blood-borne diseases to climate change, genetic alteration to text to speech programs, this may be an ancient war, but one that is breaking out into the modern world utilising the resources at hand.

Ultraviolet is also one of the most morally ambiguous takes given to the genre. It constantly reminds us that we are following an off-the-books death squad, capable of carrying out extrajudicial executions with little to no oversight or consequence, sanctioned by the government and the church. It’s something that Michael struggles to come to terms with, while at the same time recognising that they are locked in a war with inhuman monsters that prey on the vulnerable.

Ultraviolet is also one of the most morally ambiguous takes given to the genre. It constantly reminds us that we are following an off-the-books death squad, capable of carrying out extrajudicial executions with little to no oversight or consequence, sanctioned by the government and the church. It’s something that Michael struggles to come to terms with, while at the same time recognising that they are locked in a war with inhuman monsters that prey on the vulnerable.

Or are they?

Demonised as masters of manipulation, the vampires claim to be an oppressed minority, driven into action by fear and superstition. They are rarely seen as the killers in Ultraviolet (at least directly), and also claim to only bring those across that want to. They are seen as very big on free choice, but also extremely capable of utilising soft power to coerce. That question of misunderstood minority, or blood-thirsty monster is a twisting narrative that plays throughout the run of the series, and only becomes clear when all the pieces are in place.

That moral ambiguity is also something that plays at all the main characters, as each are constructed with an Achilles Heel, and it’s a thread which Ultraviolet has no qualms in pulling to spur conflict. Heck, the fractious relationship between Michael and Vaughan, is as much driven by Vaughan’s attempts to purge a mirrored weakness from a new recruit (Michael’s attachment to his ex-partner’s fiancee), as by any differing methodology or ideology. Friends and family are all seen as potential points of attack or coercion, and all of this is woven into the narrative to provide motivation, but also to undermine our confidence as viewers that we know how it will progress.

However it’s in tone that Ultraviolet makes itself truly something special. A deep sense of melancholia is built into the very bones of this show – characters, themes, script, Sue Hewitt’s mournful minimalist score, and its elegantly slow execution. This is something expected of the vampires, as they’ve been portrayed as wangst-ridden goths long before Lugosi ever donned a cape, but it’s the humans I’m referring to. Their fragility stems from loss, and a realisation of what they are fighting against. They are trying to hold a line, while recognising the frailness of their civilisation, and their own life. Ultraviolet revels in this creating something of crystalline beauty, where it could easily make something camp or vulgar.

The zenith of this probably comes in the episode Terra Incognita, when Vaughan is locked in a warehouse with four sealed coffins counting down to sunset. Clearly soon to be overmatched and with no help at hand, Vaughan realises his own demise is imminent and contemplates suicide. Elba makes this one of the most memorable scenes of the ’90s as you can clearly see his quiet rage, and plaintive cry for something else, giving us every indication of his future stardom. Yet it is these wonderful character moments that Ultraviolet delights in giving us, and just one of many, allowing each member of the exceptional cast a chance to shine.

The zenith of this probably comes in the episode Terra Incognita, when Vaughan is locked in a warehouse with four sealed coffins counting down to sunset. Clearly soon to be overmatched and with no help at hand, Vaughan realises his own demise is imminent and contemplates suicide. Elba makes this one of the most memorable scenes of the ’90s as you can clearly see his quiet rage, and plaintive cry for something else, giving us every indication of his future stardom. Yet it is these wonderful character moments that Ultraviolet delights in giving us, and just one of many, allowing each member of the exceptional cast a chance to shine.

The result is a “one and done” masterpiece, throwing everything into the first season to give us a glimpse at a nocturne world. Although considered for an American adaption, thankfully that fell over (although there should be a 2000 Fox pilot out in the TV ether for those of strong constitution), but the process forced series creator Joe Ahearne to realise that creatively there was nothing left in the tank for a second season. As such, it’s just worth appreciating Ultraviolet for the one season wonder that it is, and something different to watch in the spooky season.