Tony Stark: Wow. Uh, bold design choice.

Eric Killmonger: What? I like anime.

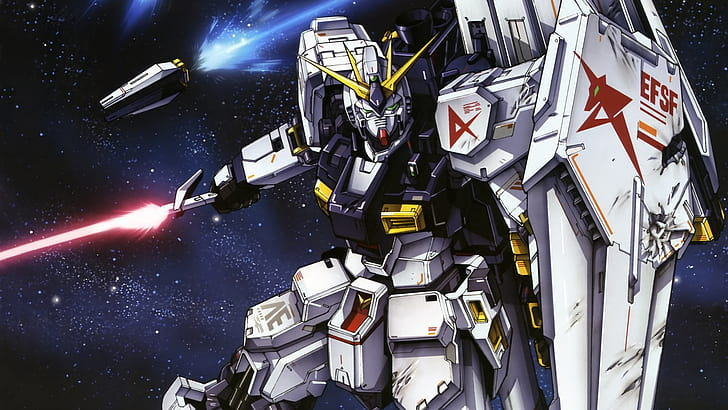

Tony Stark: Worst-case scenario, we’ll end up with the most expensive Gundam model. Jarvis, start casing the warehouse. We’re gonna need FPV wiring, nanocircuitry, and Bloody Marys. Hangover’s starting to kick in.”

What If…? Ep 6

With the premiere of Hathaway prompting Netflix to release a treasure trove of Gundam last month, a few of my friends have been asking how to best get into this Japanese cultural icon. After all, over four decades worth of media spanning multiple timelines is daunting for the casual viewer. For example, if you were to delve into Hathaway, you would be watching a film series whose protagonist is a legacy character with ties back to the first very first series of Mobile Suit Gundam, and has previously appeared in the series Zeta Gundam and film Char’s Counterattack ( the last is referenced in numerous direct callbacks in Hathaway, and is key to Hathaway Noa’s motivation).

So it’s complicated, but it’s hard to overstate the importance of this genre defining show. Without it we wouldn’t have had Robotech, or be worried about reactor shutdowns in Mechwarrior, and both Evangelion and Pacific Rim would have been a damn sight different. So sit down, strap yourself in, fire up the Minovsky particles, and let’s begin the training.

What is Gundam ?

Archer: For all we know, they’re building a Gundam suit with bazookas for hands.

Archer S3 ep9

Premiering in 1979, Mobile Suit Gundam was a 43 episode anime series centred around the tituallar robot (well, mecha) and it’s young, inexperienced pilot, Amuro Ray, as they are thrust into a bloody conflict engulfing humanity’s future. Although low rating at the time of release, it built a fanbase through models, manga, and subsequent theatrical releases to spawn an entirely new genre. Unlike other giant robot shows at the time, which fell into the Super Robot genre, Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Mobile Suit Gundam drew on inspiration from Heinlein’s Starship Troopers and Space Battleship Yamato to create something with a harder military sci-fi edge.

Premiering in 1979, Mobile Suit Gundam was a 43 episode anime series centred around the tituallar robot (well, mecha) and it’s young, inexperienced pilot, Amuro Ray, as they are thrust into a bloody conflict engulfing humanity’s future. Although low rating at the time of release, it built a fanbase through models, manga, and subsequent theatrical releases to spawn an entirely new genre. Unlike other giant robot shows at the time, which fell into the Super Robot genre, Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Mobile Suit Gundam drew on inspiration from Heinlein’s Starship Troopers and Space Battleship Yamato to create something with a harder military sci-fi edge.

It envisioned a world with no aliens, only a conflict between humanity and its spaceborn descendants. Here a new form of armoured fighting machine, the mobile suit, had arisen from the battlefield to assert dominance. This piloted bipedal mechanised armour was able not only to operate in multiple environments (including space), but had been able to fill a niche created by advances in ECM warfare, to dominate the close quarters fighting that had become the norm. The result was not just to create the Real Robot genre, but to also demonstrate that anime as a medium could tackle more complex themes and characters. Mobile Suit Gundam dealt with the trauma of war and the price it had on the people, the environment, and politics of the period, often shifting its view to cover both sides of the One Year War.

Since that inception Gundam has gone on to become a massive intellectual property encompassing 50 odd films and tv series, as well as numerous mangas, and computer games. It spans the breadth of genres, from chiba-style comedy, to real world collecting, to military sci-fi, and stretches across multiple alternative timelines. That is where Gundam can become complicated for a casual viewer.

The different universes of Gundam

“It is the year 0079 of the Universal Century. A half-century has passed since Earth began moving its burgeoning population into gigantic orbiting space colonies. A new home for mankind, where people are born and raised. And die. “

Mobile Suit Gundam

By now, thanks to Marvel, most of us are familiar with the idea of the multiverse. For Gundam, that glorious purpose comes not in the form of one simple change but rather a radically divergent future, allowing each series to start in a vastly different way. Across those multiple series of Gundam unique universes have opened up as different tales have been told, with the only similarity being that there is a Gundam model mobile suit, usually as the hero mech in the show (although even here there are exceptions). Some of these universes resemble our own world (in the case of the model-focused Build series), others are fantasy worlds inhabited by chiba mobile suits brought to life (in the case of SD series), but most are near-future war-torn societies where the issues plaguing our current era have been magnified by humankind’s attempts to colonise the solar system.

By now, thanks to Marvel, most of us are familiar with the idea of the multiverse. For Gundam, that glorious purpose comes not in the form of one simple change but rather a radically divergent future, allowing each series to start in a vastly different way. Across those multiple series of Gundam unique universes have opened up as different tales have been told, with the only similarity being that there is a Gundam model mobile suit, usually as the hero mech in the show (although even here there are exceptions). Some of these universes resemble our own world (in the case of the model-focused Build series), others are fantasy worlds inhabited by chiba mobile suits brought to life (in the case of SD series), but most are near-future war-torn societies where the issues plaguing our current era have been magnified by humankind’s attempts to colonise the solar system.

The original of these The Universal Century (UC) is the most fleshed out of the universes, with the later half of the initial conflict between the space-born Zeon forces and the Earth-centric Federation, known as the “One Year War” being the setting for Mobile Suit Gundam. This series has seen the timeline pushed forward almost a century into its future, as well as exploring elements leading up to the tragic conflict, and a lot in between. The UC timeline contains dozens of series, films, and manga series that not merely tell of the epic conflict between Amuro Ray (the pilot of the Gundam RX78-2) and Char Aznable (a famous Zeon Ace known as the Red Comet with a secret agenda all his own), but numerous side stories happening during that time, as well as the historical effects those conflicts have had on humanity. My personal favourite timeline, this all ties in together, but you need a lot of red string and a conspiracy board to explain it all.

Most of the other timelines only cover one or two series, and allow for a much more condensed viewing experience. There’s the After Colony timeline (AC) of Gundam Wing, which was the first Gundam series screened in America through Toonami, and hence has huge popularity, and the first to move the character focus of the show from a single protagonist to a more “boy band with mechs” style. There’s the Cosmic Era of Gundam Seed, which is in many ways a more modern retelling of the initial series. One of the timelines actually matches up with our own world as Gundam 00 uses the AD system to track dates. Heck, if you are into wrestling, then there’s the bizarre and often cringeworthy Mobile Fighter G Gundam’s Future Century (seriously there’s a Gundam based off a windmill in this show). Finally if you are really into craziness there are even attempts to coalesce all these timelines into one cohesive far future whole with a mustachioed Gundam designed by respected futurist Syd Mead in Turn A Gundam.

Most of the other timelines only cover one or two series, and allow for a much more condensed viewing experience. There’s the After Colony timeline (AC) of Gundam Wing, which was the first Gundam series screened in America through Toonami, and hence has huge popularity, and the first to move the character focus of the show from a single protagonist to a more “boy band with mechs” style. There’s the Cosmic Era of Gundam Seed, which is in many ways a more modern retelling of the initial series. One of the timelines actually matches up with our own world as Gundam 00 uses the AD system to track dates. Heck, if you are into wrestling, then there’s the bizarre and often cringeworthy Mobile Fighter G Gundam’s Future Century (seriously there’s a Gundam based off a windmill in this show). Finally if you are really into craziness there are even attempts to coalesce all these timelines into one cohesive far future whole with a mustachioed Gundam designed by respected futurist Syd Mead in Turn A Gundam.

Despite the diverse array of choices, one thing a lot of Gundam has in common is to explore confronting and complex themes, and allow a space for those to be discussed. It might just be a giant robot anime, but it is far from mindless.

Recurring themes

“Since most of these stories were written from one standpoint, I felt it would be nice to have a story showing both sides from an overhead angle. And after that it was making the TV series a long one, even though it’s a robot anime. I supposed the war setting would provide a lot of material to depict for both sides, and in Gundam, I aimed to create a story capturing both allies and enemies. Especially since anime is something people usually watch at a younger age, if you only tell about the principles and the position of one side, you will inevitably end up influencing their thoughts in a sense. This had me concerned, which was the other reason I put great care into looking at the situation—war—from a high angle.”

Yoshiyuki Tomino

With its more realistic take on the genre Tomino was able to introduce and refine themes in both subsequent series, and the movie adaption of Mobile Suit Gundam. Although there are definitely heroes and villains in the show, it is rarely a case of one side being entirely in the right. For example, there is much that is just about the initial Zeon push for independence… before it gets hijacked by a powerful family of Nazi cosplayers. Similarly, despite the close identification with the Allied powers of World War II, the Federation is also capable of atrocities, corruption, and the tacit support of an elite status quo. There is a very good reason that the script is flipped in the sequel series, Zeta Gundam, with a more authoritarian version of the Federation (the Titans) becoming the villains for the series. In a Japan dealing with the psychological damage done to and by it in the last war, it is little wonder that Tomino envisioned this messy conflict as a rack for his characters. One where the best and brightest on both sides are often broken – physically, mentally, and spiritually.

With its more realistic take on the genre Tomino was able to introduce and refine themes in both subsequent series, and the movie adaption of Mobile Suit Gundam. Although there are definitely heroes and villains in the show, it is rarely a case of one side being entirely in the right. For example, there is much that is just about the initial Zeon push for independence… before it gets hijacked by a powerful family of Nazi cosplayers. Similarly, despite the close identification with the Allied powers of World War II, the Federation is also capable of atrocities, corruption, and the tacit support of an elite status quo. There is a very good reason that the script is flipped in the sequel series, Zeta Gundam, with a more authoritarian version of the Federation (the Titans) becoming the villains for the series. In a Japan dealing with the psychological damage done to and by it in the last war, it is little wonder that Tomino envisioned this messy conflict as a rack for his characters. One where the best and brightest on both sides are often broken – physically, mentally, and spiritually.

This has allowed for some complex characterisation, perhaps none more so than in the two initial protagonists. Although Amuro Ray starts as a typical bright and dedicated young hero, he undergoes a pretty unique hero’s journey while refusing “the call to adventure” – one that involves PTSD, military correction, and witnessing a ton of civilian casualties. By the end of this journey, he’s quite a complex character that has battled with depression and despair throughout his military service, and has been able to find a way he can serve that meets his moral standards. Most importantly, he’s still able to be hopeful which, combined with his strong moral compass, brings about some positivity at the end of Char’s Counterattack.

However, as good as Amuro Ray is, there is no doubt that Char is the stand out character of the series. Established as a villain in the initial Mobile Suit Gundam, Char reveals himself to be far more complex and nuanced than just a mere well-honed foil to Amuro’s heroic persona. Char is shown to have his own personal agenda beyond merely furthering Zeon, but is also a genuine believer in the cause of spacenoid indepence. Throughout the three series he shifts from villain, to antihero, to mentor, and back to tragic villain (albeit with a noble stated intention). His journey mirrors Amuro’s in some ways, and there is little doubt that he’s tragically broken by the end of Char’s Counterattack despite his power being in its ascendancy. It’s a fascinating exploration, and one not really told in anime before this time, so it’s little wonder that the Red Comet. as he is known, became such a fan favourite of the franchise.

All this characterization is brought out by perhaps the most common theme of the Gundam universe – “war is hell”. Although it might glorify the machinery, and ostensibly be there to sell model kits to teenage boys, Gundam rarely shys away from a graphic portrayal of war. The very first episode sees civilian friends and families of main characters carelessly taken out as collateral damage right before our eyes. As the series progressed it has shown the ability to maim, debilitate, and kill main characters. The ending of Zeta Gundam is considered by many to be one of the darkest endings of any anime.

All this characterization is brought out by perhaps the most common theme of the Gundam universe – “war is hell”. Although it might glorify the machinery, and ostensibly be there to sell model kits to teenage boys, Gundam rarely shys away from a graphic portrayal of war. The very first episode sees civilian friends and families of main characters carelessly taken out as collateral damage right before our eyes. As the series progressed it has shown the ability to maim, debilitate, and kill main characters. The ending of Zeta Gundam is considered by many to be one of the darkest endings of any anime.

In obeying the tropes of the super robot genre by casting a young boy as the hero it also looks at the use of child soldiers, a trope that it later expands into the exploitation of other minorities in warfare (particularly in the weaponization of Newtypes and cyber newtypes). Although this runs for much of Gundam, paralleling much of late World War II (where increasingly younger and untrained troops were thrown into the frontline) it is really taken to the logical and terrifying extreme in Iron Blooded Orphan, which sees a mercenary company of child slaves fighting for freedom and recognition.

However that’s not to say it’s all dated well. Tomino seems incapable of writing for women, and a lot of the tropes employed there are often outdated. True, we see capable women operating on the frontlines, but the need for a romantic subplot often undercuts this strength as they become subservient when confronted by matters of the heart. This can lead to some unstable portrayals, many bordering on the completely psychotic, even when they are meant to be tragically romantic (with Quess from Char’s Counterattack being perhaps the worst example).

Then there’s the matter of military correction, the straight up extra-judicial physical abuse meted out to subordinates as a form of discipline. Gundam has a strange relationship with this, showing it as part of the operation of a military unit (and at the time of production, it totally would have been), and alternating between being for and against it. It really does sit uneasily with modern audiences, but it is also hard to deny that this has certainly been part of military procedure in the past.

So where to start?

“I finally understand now, Mika. We don’t need any destinations. We just need to keep moving forward. As long as we don’t stop, the road will continue. I’m not stopping. As long as you all don’t stop, I’ll be at the end waiting for you. So hear me well. Don’t you ever stop.”

Orga Itsuka Gundam: Iron Blooded Orphans

After all that, it’s back to the main question, where to start? However, the answer to that is not an entirely easy one. Given the large amount of Gundam that’s been produced in many different timelines, there’s a staggering amount of options, but these would be the three I’d recommend.

After all that, it’s back to the main question, where to start? However, the answer to that is not an entirely easy one. Given the large amount of Gundam that’s been produced in many different timelines, there’s a staggering amount of options, but these would be the three I’d recommend.

First off, the quick and dirty route. If you’re not fussed with spoilers, look for a “things you need to know before watching Hathaway” video, and then dive into Hathaway. You’ll miss out on much of the nuance of the world, but you will be able to experience the latest animation, and an exceptional example of the franchise that covers many of the themes mentioned above. In fact, Hathaway might have one of the best examples of the collateral damage of war, as one of the chief sequences is a mobile suit fight as seen from the perspective of fleeing civilians. It’s a terrifying encounter and clearly displays the casual destructive potential of these armoured goliaths.

Then if you like what you see, you can backtrack later and watch the previous films. The downside is it’ll require heavy spoilers for the previous shows of the franchise, but the upside is this will take the least amount of time.

The second option is to watch the three Mobile Suit Gundam films and Char’s Counterattack, before watching Hathaway. This is the preferred option, as it’ll give you a fairly comprehensive guide to the Universal Century, and it’s all readily available on Netflix. The first three films are mostly a cutdown version of the series for theatrical release, but are refined to carry the essential information of the plot that Tomino wanted to tell, hence representing the clearest telling of the tale (without studio or sponsor interference, which the initial series suffered from). The downside is this marks a substantial investment in time, and you need to get used to some very dated animation (although for the time it was pretty impressive), before getting to some cleaner and more exciting version.

The final option is to try something different, and look at a stand alone series. Gundam:Iron Blooded Orphans is a good example of recent Gundam that stands alone from the tangled continuity of the Universal Century, while touching on many of the same themes and conveying some intense mecha combat. This might appeal more to modern anime sensibilities, while still giving a little hint of the classic. It’s also available on Netflix, making it readily available. Alternatively, if you did want something UC related, then a search of YouTube would probably give you unofficial access to either Mobile Suit Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket or Mobile Suit Gundam: The 08th MS Team. Both are excellent stand alone tales set in the One Year War, and represent some of the finest storytelling the series has to offer.

What it amounts to, is that for over 40 years Gundam has been a fine example of the mecha genre in anime, providing a lot of scope for fans to enjoy giant robot action. For those with a somewhat hard sci-fi bent, we have been exceptionally well catered for with excellent animation, characterisation, and storylines. For those of you yet to experience that magic, well, there’s a wealth of material out there, with enough variety to appeal to almost everyone’s tastes.